en esta pagina

- Lista de los Regimientos del U.S.C.T. que llegaron a Texas

- Los Primeros Regimientos Negros en llegar a Texas

- El Cambio de la Misión del Tribunal Supremo de los Estados Unidos en Texas

- El Mito vs. la Realidad: El USCT y Juneteenth

- El Tribunal de Apelaciones de los Estados Unidos en la Frontera – Soldados Negros y Comunidad en la Zona Fronteriza

The Listing of the U.S.C.T. Regiments that came to Texas

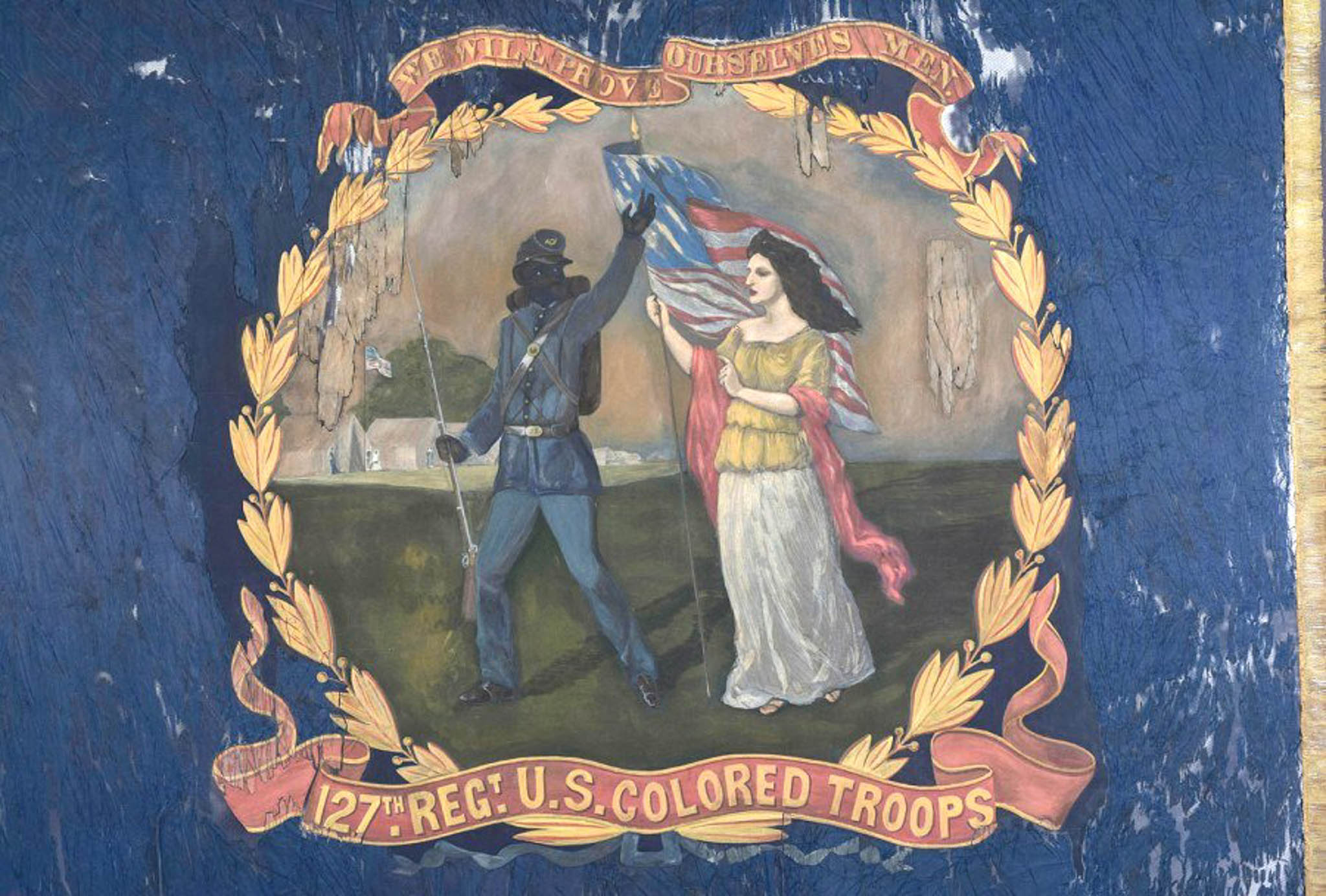

1864 Battle Flag, 127th Regiment U.S. Colored Troops by David Bustill Bowser | Library of Congress

Lista de los regimientos del USCT que llegaron a Texas

Bandera de batalla de 1864, 127.º Regimiento de Tropas Negras de EE. UU., por David Bustill Bowser | Biblioteca del Congreso

The First Black Regiments to arrive in Texas

The first Black Union Regiments began to arrive in Texas following the failed Sabine River Expedition in the Fall of 1863. While the primary objective of the expedition of capturing Galveston failed, Union regiments were able to capture posts on the barrier islands and critical fortifications near Brownsville that could hamper the shipping of Confederate Cotton to Mexico.

Among the first regiments to arrive to occupy Brazos Santiago would be the 16th Infantry Regiment of the Corps D’Afrique, 1st Engineers Regiment of the Corps D”Afrique, and the 3rd Engineer Regiment of the Corps D’Afrique in October 1863. They would go on to support Union Forces during the Battle of Brownsville in November 1863 followed up by the 2nd Engineer Regiment of Corps D’Afrique and the 13th Infantry Regiment of the Corps D’Afrique in December 1863.

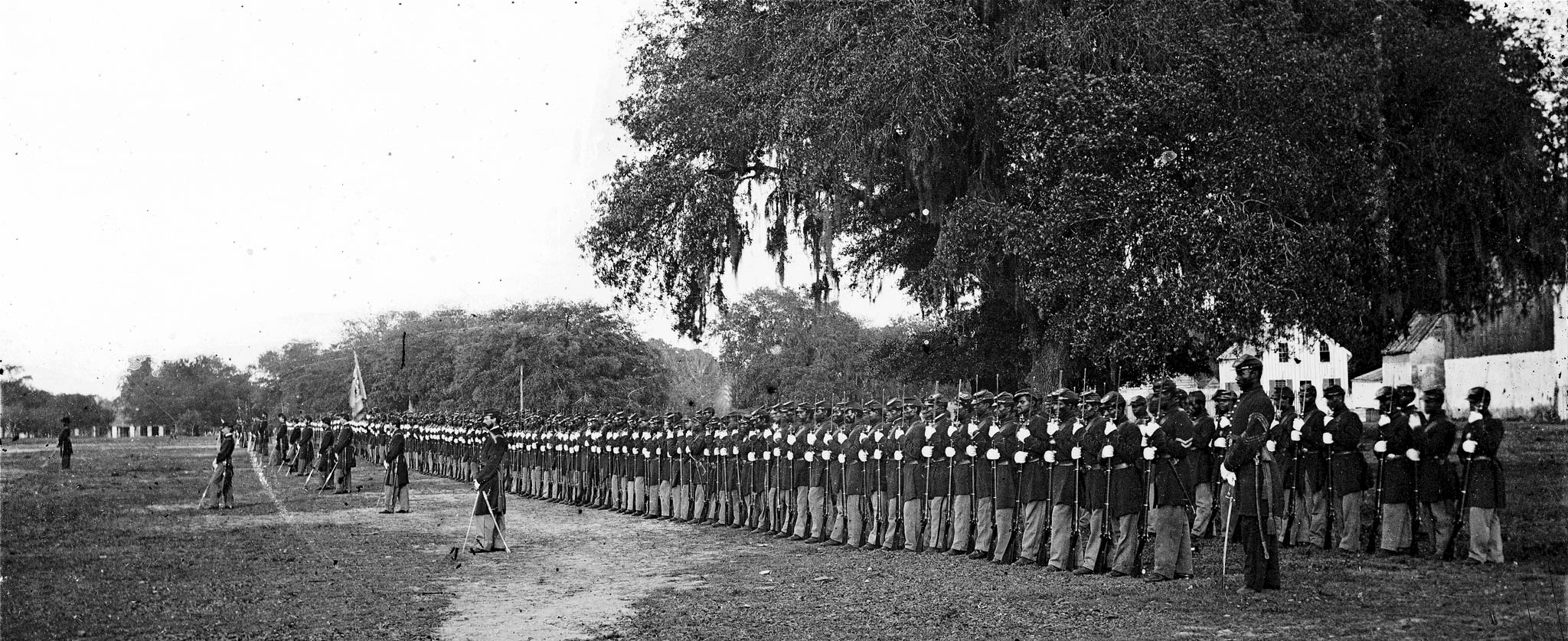

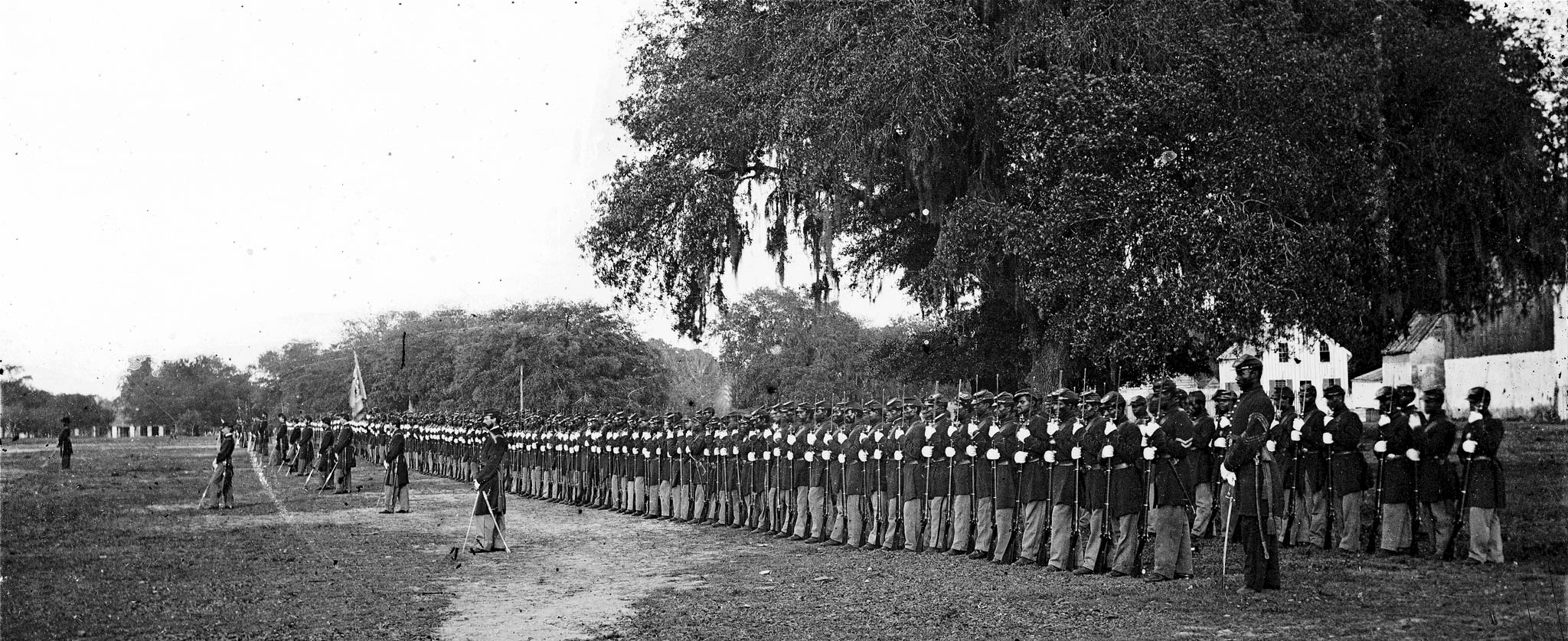

2nd US Colored Cavalry | Library of Congress

In addition to hampering the Confederate supply lines connecting them to the rest of the world via Matamoros and Brownsville, they would be responsible for constructing fortifications and infrastructure along with helping load and offload Union ships bringing supplies to the area. By April of 1864, the 2nd and 3rd Engineer Regiments of the Corps D’Afrique would leave Texas and return to New Orleans for conversion into the 96th and 97th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiments. The 1st Engineer Regiment of the Corps D’Afrique along with the 13th and 16th Infantry Regiments of the Corp’s D”Afrique would remain in Texas well into the summer of 1864 to be converted into the 95th, 85th, and 87th U.S. Colored Infantry Regiments

Los primeros regimientos negros en llegar a Texas

Los primeros regimientos negros de la Unión comenzaron a llegar a Texas tras la fallida expedición del río Sabine en el otoño de 1863. Si bien el objetivo principal de la expedición, capturar Galveston, fracasó, los regimientos de la Unión lograron capturar puestos en las islas barrera y fortificaciones cruciales cerca de Brownsville que podrían obstaculizar el envío de algodón confederado a México.

Entre los primeros regimientos en llegar para ocupar Brazos Santiago se encontraban el 16.º Regimiento de Infantería del Cuerpo de África, el 1.º Regimiento de Ingenieros del Cuerpo de África y el 3.º Regimiento de Ingenieros del Cuerpo de África en octubre de 1863. Posteriormente, apoyarían a las Fuerzas de la Unión durante la Batalla de Brownsville en noviembre de 1863, seguidos por el 2.º Regimiento de Ingenieros del Cuerpo de África y el 13.º Regimiento de Infantería del Cuerpo de África en diciembre de 1863.

2.º Regimiento de Caballería de Color de EE. UU. | Biblioteca del Congreso

The Changing of the U.S.C.T.’s Mission in Texas

Following the battle and subsequent capture of Brownsville from the Confederacy, the Union Army had two primary objectives.

- To deny the Confederates in Texas a means of income via the trade of cotton and other essential commodities to both Mexico and European Nations.

- To provide a body of troops to act as a symbolic display that the Federal Government, in spite of fighting a Civil War, would take steps to enforce the Monroe Doctrine of the 1820s and counter the possible spread of Emperor Maximillian’s power and influence into U.S. controlled territories.

29th Connecticut Colored Infantry Regiment, Beaufort, South Carolina (cropped) | Library of Congress

These objectives would also apply to the Regiments from the Corps D’Afrique that would initially arrive in Texas. However, as the tide of the Civil War would change in the favor of the Union Army and the Confederacy would lose ground, the newly christened U.S. Colored Troop regiments that were stationed in Texas would have other objectives added.

Following the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation in conjunction with the Confiscation Acts of 1861 and 1862, the U.S. Colored Troops, alongside the rest of the Union Army, would also be tasked with protecting enslaved people who escaped to areas under their control as “contraband” or seized enemy property from slave catchers.

Contrabands at Headquarters of General Lafayette by Mathew Brady | Library of Congress

El cambio de la misión del Tribunal Supremo de los Estados Unidos en Texas

Tras la batalla y la posterior toma de Brownsville a la Confederación, el Ejército de la Unión tenía dos objetivos principales:

- Privar a los confederados de Texas de una fuente de ingresos mediante el comercio de algodón y otros productos esenciales tanto para México como para las naciones europeas.

- Proporcionar un cuerpo de tropas que sirviera como muestra simbólica de que el Gobierno Federal, a pesar de librar una Guerra Civil, tomaría medidas para aplicar la Doctrina Monroe de la década de 1820 y contrarrestar la posible expansión del poder e influencia del emperador Maximiliano a los territorios controlados por Estados Unidos.

29.º Regimiento de Infantería de Color de Connecticut, Beaufort, Carolina del Sur (recortado) | Biblioteca del Congreso

Estos objetivos también se aplicarían a los regimientos del Cuerpo de África que llegarían inicialmente a Texas. Sin embargo, a medida que la marea de la Guerra Civil cambiaría a favor del Ejército de la Unión y la Confederación perdería terreno, los recién bautizados regimientos de Tropas de Color de EE. UU. que estaban estacionados en Texas tendrían otros objetivos agregados.

Tras la aprobación de la Proclamación de Emancipación junto con las Leyes de Confiscación de 1861 y 1862, las Tropas de Color de EE. UU., junto con el resto del Ejército de la Unión, también tendrían la tarea de proteger a las personas esclavizadas que escapaban a áreas bajo su control como “contrabando” o confiscaban propiedad enemiga a los cazadores de esclavos.

Contrabando en el cuartel general del general Lafayette por Mathew Brady | Biblioteca del Congreso

The Myth VS. The Reality – The U.S.C.T. and Juneteenth

A common belief surrounding Juneteenth is that the U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) were brought to Texas specifically to enforce General Order No. 3 and liberate the enslaved. While it is true that Black regiments arrived in Texas following the Civil War, the full story is more complex.

Many of these regiments were stationed in South Texas towns like Indianola and Brownsville—regions with significantly smaller enslaved populations compared to Galveston and Houston. Historical records and personal testimonies indicate that interactions between U.S.C.T. soldiers and newly freed Black communities were rare, particularly in major cities where emancipation was announced. In fact, some documents suggest that Black regiments were deliberately positioned in South Texas not just for occupation duty and border security, but also to minimize the possibility of Black soldiers inspiring resistance among the local Black population.

El mito vs. la realidad: El USCT y Juneteenth

Una creencia común en torno al Juneteenth es que las Tropas de Color de los Estados Unidos (USCT) fueron traídas a Texas específicamente para hacer cumplir la Orden General N.° 3 y liberar a los esclavos. Si bien es cierto que los regimientos negros llegaron a Texas después de la Guerra Civil, la historia completa es más compleja.

Muchos de estos regimientos estaban estacionados en pueblos del sur de Texas como Indianola y Brownsville, regiones con poblaciones de esclavos significativamente menores en comparación con Galveston y Houston. Los registros históricos y los testimonios personales indican que las interacciones entre los soldados del USCT y las comunidades negras recién liberadas eran poco frecuentes, especialmente en las grandes ciudades donde se anunció la emancipación. De hecho, algunos documentos sugieren que los regimientos negros se desplegaron deliberadamente en el sur de Texas no solo para tareas de ocupación y seguridad fronteriza, sino también para minimizar la posibilidad de que los soldados negros inspiraran resistencia entre la población negra local.

The U.S.C.T. on the Border – Black Soldiers and Community in the Borderlands

The arrival of the 25th Corps to towns along the Mexico-Texas border brought a significant increase in the Black population within a short period. However, Black presence in the region was not entirely new. Since the abolition of slavery in Mexico in 1837, many formerly enslaved individuals escaped from Texas plantations to Mexico, aided by a network of abolitionists who guided them to border towns for safe passage. Some chose to stay, integrating into local communities that were generally more accepting and opposed to slavery.

Despite facing challenges like disease and harsh environmental conditions, many soldiers of the 25th Corps spoke highly of the local population, reflecting on the positive relationships they built during their time stationed in the borderlands.

El Tribunal de Apelaciones de los Estados Unidos en la Frontera – Soldados Negros y Comunidad en la Zona Fronteriza

Juneteenth @160

Terms & Conditions

Juneteenth @160